Rethinking Renewable Mandates

Powering the world’s economy with wind, water and solar, and

perhaps a little wood sounds like a good idea until a person looks at

the details. The economy can use small amounts of wind, water and solar,

but adding these types of energy in large quantities is not necessarily

beneficial to the system.

While a change to renewables may, in theory, help save world ecosystems, it will also tend to make the electric grid increasingly unstable. To prevent grid failure, electrical systems will need to pay substantial subsidies to fossil fuel and nuclear electricity providers that can offer backup generation when intermittent generation is not available. Modelers have tended to overlook these difficulties. As a result, the models they provide offer an unrealistically favorable view of the benefit (energy payback) of wind and solar.

If the approach of mandating wind, water, and solar were carried far enough, it might have the unfortunate effect of saving the world’s ecosystem by wiping out most of the people living within the ecosystem. It is almost certain that this was not the intended impact when legislators initially passed the mandates.

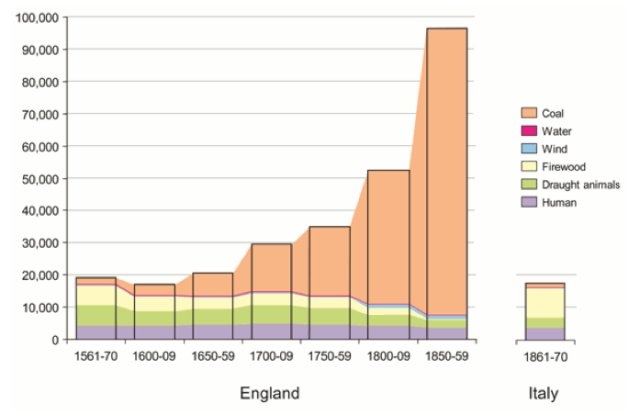

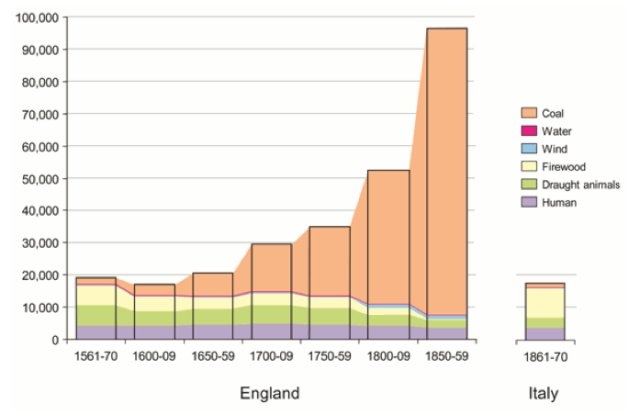

[1] History suggests that in the past, wind and water never provided a very large percentage of total energy supply.

Figure 1 shows that before and during the Industrial Revolution, wind

and water energy provided 1% to 3% of total energy consumption.

Figure 1 shows that before and during the Industrial Revolution, wind

and water energy provided 1% to 3% of total energy consumption.

For an energy source to work well, it needs to be able to produce an adequate “return” for the effort that is put into gathering it and putting it to use. Wind and water seemed to produce an adequate return for a few specialized tasks that could be done intermittently and that didn’t require heat energy.

When I visited Holland a few years ago, I saw windmills from the 17th and 18th centuries. These windmills pumped water out of low areas in Holland, when needed. A family would live inside each windmill. The family would regulate the level of pumping desired by adding or removing cloths over the blades of the windmill. To earn much of their income, they would also till a nearby plot of land.

This overall arrangement seems to have provided adequate income for the family. We might conclude, from the inability of wind and water energy to spread farther than 1% -3% of total energy consumption, that the energy return from the windmills was not very high. It was adequate for the arrangement I described, but it didn’t provide enough extra energy to encourage greatly expanded use of the devices.

[2] At the time of the Industrial Revolution, coal worked vastly better for most tasks of the economy than did wind or water.

Economic historian Tony Wrigley, in his book Energy and the English Industrial Revolution, discusses the differences between an organic economy (one whose energy sources are human labor, energy from draft animals such as oxen and horses, and wind and water energy) and an energy-rich economy (one that also has the benefit of coal and perhaps other energy sources). Wrigley notes the following benefits of a coal-based energy-rich economy during the period shown in Figure 1:

The name renewables reflects the fact that wind turbines, solar panels, and hydroelectric dams do not burn fossil fuels in their capture of energy from the environment.

Modern hydroelectric dams are constructed with concrete and steel. They are built and repaired using fossil fuels. Wind turbines and solar panels use somewhat different materials, but these too are available only thanks to the use of fossil fuels. If we have difficulty with the fossil fuel system, we will not be able to maintain and repair any of these devices or the electricity transmission system used for distributing the energy that they capture.

[4] With the 7.7 billion people in the world today, adequate energy supplies are an absolute requirement if we do not want population to fall to a very low level.

There is a myth that the world can get along without fossil fuels. Wrigley writes that in a purely organic economy, the vast majority of roads were deeply rutted dirt roads that could not be traversed by wheeled vehicles. This made overland transport very difficult. Canals were used to provide water transport at that time, but we have virtually no canals available today that would serve the same purpose.

It is true that buildings for homes and businesses can be built with wood, but such buildings tend to burn down frequently. Buildings of stone or brick can also be used. But with only the use of human and animal labor, and having few roads that would accommodate wheeled carts, brick or stone homes tend to be very labor-intensive. So, except for the very wealthy, most homes will be made of wood or of other locally available materials such as sod.

Wrigley’s analysis shows that before coal was added to the economy, human labor productivity was very low. If, today, we were to try to operate the world economy using only human labor, draft animals, and wind and water energy, we likely could not grow food for very many people. World population in 1650 was only about 550 million, or about 7% of today’s population. It would not be possible to provide for the basic needs of today’s population with an organic economy as described by Wrigley.

(Note that organic here has a different meaning than in “organic agriculture.” Today’s organic agriculture is also powered by fossil fuel energy. Organic agriculture brings soil amendments by truck, irrigates land and makes “organic sprays” for fruit, all using fossil fuels.)

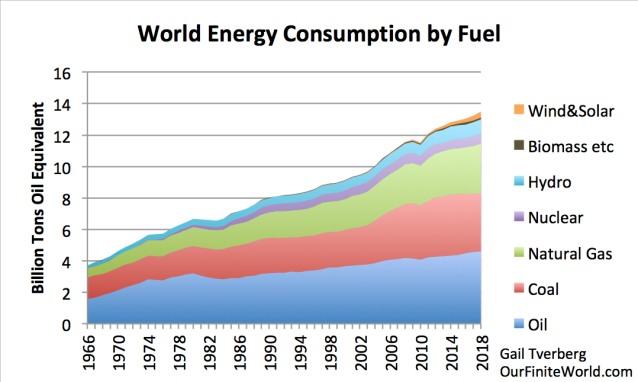

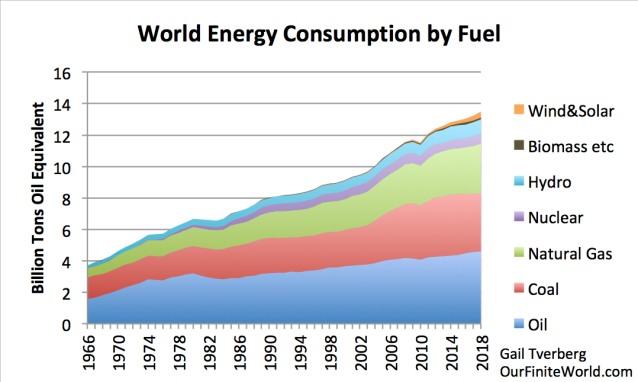

[5] Wind, water and solar only provided about 11% of the world’s total energy consumption for the year 2018. Trying to ramp up the 11% production to come anywhere close to 100% of total energy consumption seems like an impossible task.

Let’s look at what it would take to ramp up the current renewables

percentage from 11% to 100%. The average growth rate over the past five

years of the combined group that might be considered renewable (Hydro +

Biomass etc + Wind&Solar) has been 5.8%. Maintaining such a high

growth rate in the future is likely to be difficult because new

locations for hydroelectric dams are hard to find and because biomass

supply is limited. Let’s suppose that despite these difficulties, this

5.8% growth rate can be maintained going forward.

Let’s look at what it would take to ramp up the current renewables

percentage from 11% to 100%. The average growth rate over the past five

years of the combined group that might be considered renewable (Hydro +

Biomass etc + Wind&Solar) has been 5.8%. Maintaining such a high

growth rate in the future is likely to be difficult because new

locations for hydroelectric dams are hard to find and because biomass

supply is limited. Let’s suppose that despite these difficulties, this

5.8% growth rate can be maintained going forward.

To increase the quantity from 2018’s low level of renewable supply to the 2018 total energy supply at a 5.8% growth rate would take 39 years. If population grows between 2018 and 2057, even more energy supply would likely be required. Based on this analysis, increasing the use of renewables from a 11% base to close to a 100% level does not look like an approach that has any reasonable chance of fixing our energy problems in a timeframe shorter than “generations.”

The situation is not quite as bad if we look at the task of producing an amount of electricity equal to the world’s current total electricity generation with renewables (Hydro + Biomass etc + Wind&Solar); renewables in this case provided 26% of the world’s electricity supply in 2018.

The catch with replacing electricity (Figure 3) but not energy

supplies is the fact that electricity is only a portion of the world’s

energy supply. Different calculations give different percentages, with

electricity varying between 19% to 43% of total energy consumption.1

Either way, substituting wind, water and solar in electricity

production alone does not seem to be sufficient to make the desired

reduction in carbon emissions.

The catch with replacing electricity (Figure 3) but not energy

supplies is the fact that electricity is only a portion of the world’s

energy supply. Different calculations give different percentages, with

electricity varying between 19% to 43% of total energy consumption.1

Either way, substituting wind, water and solar in electricity

production alone does not seem to be sufficient to make the desired

reduction in carbon emissions.

[6] A major drawback of wind and solar energy is its variability from hour-to-hour, day-to-day, and season-to-season. Water energy has season-to-season variability as well, with spring or wet seasons providing the most electricity.

Back when modelers first looked at the variability of electricity produced by wind, solar and water, they hoped that as an increasing quantity of these electricity sources were added, the variability would tend to offset. This happens a little, but not nearly as much as one would like. Instead, the variability becomes an increasing problem as more is added to the electric grid.

When an area first adds a small percentage of wind and/or solar electricity to the electric grid (perhaps 10%), the electrical system’s usual operating reserves are able to handle the variability. These were put in place to handle small fluctuations in supply or demand, such as a major coal plant needing to be taken off line for repairs, or a major industrial client reducing its demand.

But once the quantity of wind and/or solar increases materially, different strategies are needed. At times, production of wind and/or solar may need to be curtailed, to prevent overburdening the electric grid. Batteries are likely to be needed to help ease the abrupt transition that occurs when the sun goes down at the end of the day while electricity demand is still high. These same batteries can also help ease abrupt transitions in wind supply during wind storms.

Apart from brief intermittencies, there is an even more serious problem with seasonal fluctuations in supply that do not match up with seasonal fluctuations in demand. For example, in winter, electricity from solar panels is likely to be low. This may not be a problem in a warm country, but if a country is cold and using electricity for heat, it could be a major issue.

The only real way of handling seasonal intermittencies is by having fossil fuel or nuclear plants available for backup. (Battery backup does not seem to be feasible for such huge quantities for such long periods.) These back-up plants cannot sit idle all year to provide these services. They need trained staff who are willing and able to work all year. Unfortunately, the pricing system does not provide enough funds to adequately compensate these backup systems for those times when their services are not specifically required by the grid. Somehow, they need to be paid for the service of standing by, to offset the inevitable seasonal variability of wind, solar and water.

[7] The pricing system for electricity tends to produce rates that are too low for those electricity providers offering backup services to the electric grid.

As a little background, the economy is a self-organizing system that operates through the laws of physics. Under normal conditions (without mandates or subsidies) it sends signals through prices and profitability regarding which types of energy supply will “work” in the economy and which kinds will simply produce too much distortion or create problems for the system.

If legislators mandate that intermittent wind and solar will be allowed to “go first,” this mandate is by itself a substantial subsidy. Allowing wind and solar to go first tends to send prices too low for other producers because it tends to reduce prices below what those producers with high fixed costs require.2

If energy officials decide to add wind and solar to the electric grid when the grid does not really need these supplies, this action will also tend to push other suppliers off the grid through low rates. Nuclear power plants, which have already been built and are adding zero CO2 to the atmosphere, are particularly at risk because of the low rates. The Ohio legislature recently passed a $1.1 billion bailout for two nuclear power plants because of this issue.

If a mandate produces a market distortion, it is quite possible (in fact, likely) that the distortion will get worse and worse, as more wind and solar is added to the grid. With more mandated (inefficient) electricity, customers will find themselves needing to subsidize essentially all electricity providers if they want to continue to have electricity.

The physics-based economic system without mandates and subsidies provides incentives to efficient electricity providers and disincentives to inefficient electricity suppliers. But once legislators start tinkering with the system, they are likely to find a system dominated by very inefficient production. As the costs of handling intermittency explode and the pricing system gets increasingly distorted, customers are likely to become more and more unhappy.

[8] Modelers of how the system might work did not understand how a system with significant wind and solar would work. Instead, they modeled the most benign initial situation, in which the operating reserves would handle variability, and curtailment of supply would not be an issue.

Various modelers attempted to figure out whether the return from wind and solar would be adequate, to justify all of the costs of supporting it. Their models were very simple: Energy Out compared to Energy In, over the lifetime of a device. Or, they would calculate Energy Payback Periods. But the situation they modeled did not correspond well to the real world. They tended to model a situation that was close to the best possible situation, one in which variability, batteries and backup electricity providers were not considerations. Thus, these models tended to give a far too optimistic estimates of the expected benefit of intermittent wind and solar devices.

Furthermore, another type of model, the Levelized Cost of Electricity model, also provides distorted results because it does not consider the subsidies needed for backup providers if the system is to work. The modelers likely also leave out the need for backup batteries.

In the engineering world, I am told that computer models of expected costs and income are not considered to be nearly enough. Real-world tests of proposed new designs are first tested on a small scale and then at progressively larger scales, to see whether they will work in practice. The idea of pushing “renewables” sounded so good that no one thought about the idea of testing the plan before it was put into practice.

Unfortunately, the real-world tests that Germany and other countries have tried have shown that intermittent renewables are a very expensive way to produce electricity when all costs are considered. Neighboring countries become unhappy when excess electricity is simply dumped on the grid. Total CO2 emissions don’t necessarily go down either.

[9] Long distance transmission lines are part of the problem, not part of the solution.

Early models suggested that long-distance transmission lines might be used to smooth out variability, but this has not worked well in practice. This happens partly because wind conditions tend to be similar over wide areas, and partly because a broad East-West mixture is needed to even-out the rapid ramp-down problem in the evening, when families are still cooking dinner and the sun goes down.

Also, long distance transmission lines tend to take many years to permit and install, partly because many landowners do not want them crossing their property. In some cases, the lines need to be buried underground. Reports indicate that an underground 230 kV line costs 10 to 15 times what a comparable overhead line costs. The life expectancy of underground cables seems to be shorter, as well.

Once long-distance transmission lines are in place, maintenance is very fossil fuel dependent. If storms are in the area, repairs are often needed. If roads are not available in the area, helicopters may need to be used to help make the repairs.

An issue that most people are not aware of is the fact that above ground long-distance transmission lines often cause fires, especially when they pass through hot, dry areas. The Northern California utility PG&E filed for bankruptcy because of fires caused by its transmission lines. Furthermore, at least one of Venezuela’s major outages seems to have been related to sparks from transmission lines from its largest hydroelectric plant causing fires. These fire costs should also be part of any analysis of whether a transition to renewables makes sense, either in terms of cost or of energy returns.

[10] If wind turbines and solar panels are truly providing a major net benefit to the economy, they should not need subsidies, even the subsidy of going first.

To make wind and solar electricity producers able to compete with other electricity providers without the subsidy of going first, these providers need a substantial amount of battery backup. For example, wind turbines and solar panels might be required to provide enough backup batteries (perhaps 8 to 12 hours’ worth) so that they can compete with other grid members, without the subsidy of going first. If it really makes sense to use such intermittent energy, these providers should be able to still make a profit even with battery usage. They should also be able to pay taxes on the income they receive, to pay for the government services that they are receiving and hopefully pay some extra taxes to help out the rest of the system.

In Item [2] above, I mentioned that when coal mines were added in England, roads to the mines were substantially improved, befitting the economy as a whole. A true source of energy (one whose investment cost is not too high relative to it output) is supposed to be generating “surplus energy” that assists the economy as a whole. We can observe an impact of this type in the improved roads that benefited England’s economy as a whole. Any so-called energy provider that cannot even pay its own fair share of taxes acts more like a leech, sucking energy and resources from others, than a provider of surplus energy to the rest of the economy.

Recommendations

In my opinion, it is time to eliminate renewable energy mandates. There will be some instances where renewable energy will make sense, but this will be obvious to everyone involved. For example, an island with its electricity generation from oil may want to use some wind or solar generation to try to reduce its total costs. This cost saving occurs because of the high price of oil as fuel to make electricity.

Regulators, in locations where substantial wind and/or solar has already been installed, need to be aware of the likely need to provide subsidies to backup providers, in order to keep the electrical system operating. Otherwise, the grid will likely fail from lack of adequate backup electricity supply.

Intermittent electricity, because of its tendency to drive other providers to bankruptcy, will tend to make the grid fail more quickly than it would otherwise. The big danger ahead seems to be bankruptcy of electricity providers and of fossil fuel producers, rather than running out of a fuel such as oil or natural gas. For this reason, I see little reason for the belief by many that electricity will “last longer” than oil. It is a question of which group is most affected by bankruptcies first.

I do not see any real reason to use subsidies to encourage the use of electric cars. The problem we have today with oil prices is that they are too low for oil producers. If we want to keep oil production from collapsing, we need to keep oil demand up. We do this by encouraging the production of cars that are as inexpensive as possible. Generally, this will mean producing cars that operate using petroleum products.

(I recognize that my view is the opposite one from what many Peak Oilers have. But I see the limit ahead as being one of too low prices for producers, rather than too high prices for consumers. The CO2 issue tends to disappear as parts of the system collapse.)

Notes:

[1] BP bases its count on the equivalent fossil fuel energy needed to create the electricity; IEA counts the heat energy of the resulting electrical output. Using BP’s way of counting electricity, electricity worldwide amounts to 43% of total energy consumption. Using the International Energy Agency’s approach to counting electricity, electricity worldwide amounts to only about 19% of world energy consumption.

[2] In some locations, “utility pricing” is used. In these cases, pricing is set in a way needed to provide a fair return to all providers. With utility pricing, intermittent renewables would not be expected to cause low prices for backup producers.

While a change to renewables may, in theory, help save world ecosystems, it will also tend to make the electric grid increasingly unstable. To prevent grid failure, electrical systems will need to pay substantial subsidies to fossil fuel and nuclear electricity providers that can offer backup generation when intermittent generation is not available. Modelers have tended to overlook these difficulties. As a result, the models they provide offer an unrealistically favorable view of the benefit (energy payback) of wind and solar.

If the approach of mandating wind, water, and solar were carried far enough, it might have the unfortunate effect of saving the world’s ecosystem by wiping out most of the people living within the ecosystem. It is almost certain that this was not the intended impact when legislators initially passed the mandates.

[1] History suggests that in the past, wind and water never provided a very large percentage of total energy supply.

Figure

1. Annual energy consumption per person (megajoules) in England and

Wales 1561-70 to 1850-9 and in Italy 1861-70. Figure by Tony Wrigley, Cambridge University.

For an energy source to work well, it needs to be able to produce an adequate “return” for the effort that is put into gathering it and putting it to use. Wind and water seemed to produce an adequate return for a few specialized tasks that could be done intermittently and that didn’t require heat energy.

When I visited Holland a few years ago, I saw windmills from the 17th and 18th centuries. These windmills pumped water out of low areas in Holland, when needed. A family would live inside each windmill. The family would regulate the level of pumping desired by adding or removing cloths over the blades of the windmill. To earn much of their income, they would also till a nearby plot of land.

This overall arrangement seems to have provided adequate income for the family. We might conclude, from the inability of wind and water energy to spread farther than 1% -3% of total energy consumption, that the energy return from the windmills was not very high. It was adequate for the arrangement I described, but it didn’t provide enough extra energy to encourage greatly expanded use of the devices.

[2] At the time of the Industrial Revolution, coal worked vastly better for most tasks of the economy than did wind or water.

Economic historian Tony Wrigley, in his book Energy and the English Industrial Revolution, discusses the differences between an organic economy (one whose energy sources are human labor, energy from draft animals such as oxen and horses, and wind and water energy) and an energy-rich economy (one that also has the benefit of coal and perhaps other energy sources). Wrigley notes the following benefits of a coal-based energy-rich economy during the period shown in Figure 1:

- Deforestation could be reduced. Before coal was added, there was huge demand for wood for heating homes and businesses, cooking food, and for making charcoal, with which metals could be smelted. When coal became available, it was inexpensive enough that it reduced the use of wood, benefiting the environment.

- The quantity of metals and tools was greatly increased using coal. As long as the source of heat for making metals was charcoal from trees, the total quantity of metals that could be produced was capped at a very low level.

- Roads to mines were greatly improved, to accommodate coal movement. These better roads benefitted the rest of the economy as well.

- Farming became a much more productive endeavor. The crop yield from cereal crops, net of the amount fed to draft animals, nearly tripled between 1600 and 1800.

- The Malthusian limit on population could be avoided. England’s population grew from 4.2 million to 16.7 million between 1600 and 1850. Without the addition of coal to make the economy energy-rich, the population would have been capped by the low food output from the organic economy.

The name renewables reflects the fact that wind turbines, solar panels, and hydroelectric dams do not burn fossil fuels in their capture of energy from the environment.

Modern hydroelectric dams are constructed with concrete and steel. They are built and repaired using fossil fuels. Wind turbines and solar panels use somewhat different materials, but these too are available only thanks to the use of fossil fuels. If we have difficulty with the fossil fuel system, we will not be able to maintain and repair any of these devices or the electricity transmission system used for distributing the energy that they capture.

[4] With the 7.7 billion people in the world today, adequate energy supplies are an absolute requirement if we do not want population to fall to a very low level.

There is a myth that the world can get along without fossil fuels. Wrigley writes that in a purely organic economy, the vast majority of roads were deeply rutted dirt roads that could not be traversed by wheeled vehicles. This made overland transport very difficult. Canals were used to provide water transport at that time, but we have virtually no canals available today that would serve the same purpose.

It is true that buildings for homes and businesses can be built with wood, but such buildings tend to burn down frequently. Buildings of stone or brick can also be used. But with only the use of human and animal labor, and having few roads that would accommodate wheeled carts, brick or stone homes tend to be very labor-intensive. So, except for the very wealthy, most homes will be made of wood or of other locally available materials such as sod.

Wrigley’s analysis shows that before coal was added to the economy, human labor productivity was very low. If, today, we were to try to operate the world economy using only human labor, draft animals, and wind and water energy, we likely could not grow food for very many people. World population in 1650 was only about 550 million, or about 7% of today’s population. It would not be possible to provide for the basic needs of today’s population with an organic economy as described by Wrigley.

(Note that organic here has a different meaning than in “organic agriculture.” Today’s organic agriculture is also powered by fossil fuel energy. Organic agriculture brings soil amendments by truck, irrigates land and makes “organic sprays” for fruit, all using fossil fuels.)

[5] Wind, water and solar only provided about 11% of the world’s total energy consumption for the year 2018. Trying to ramp up the 11% production to come anywhere close to 100% of total energy consumption seems like an impossible task.

Figure 2. World Energy Consumption by Fuel, based on data of 2019 BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

To increase the quantity from 2018’s low level of renewable supply to the 2018 total energy supply at a 5.8% growth rate would take 39 years. If population grows between 2018 and 2057, even more energy supply would likely be required. Based on this analysis, increasing the use of renewables from a 11% base to close to a 100% level does not look like an approach that has any reasonable chance of fixing our energy problems in a timeframe shorter than “generations.”

The situation is not quite as bad if we look at the task of producing an amount of electricity equal to the world’s current total electricity generation with renewables (Hydro + Biomass etc + Wind&Solar); renewables in this case provided 26% of the world’s electricity supply in 2018.

Figure 3. World electricity production by type, based on data from 2019 BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

[6] A major drawback of wind and solar energy is its variability from hour-to-hour, day-to-day, and season-to-season. Water energy has season-to-season variability as well, with spring or wet seasons providing the most electricity.

Back when modelers first looked at the variability of electricity produced by wind, solar and water, they hoped that as an increasing quantity of these electricity sources were added, the variability would tend to offset. This happens a little, but not nearly as much as one would like. Instead, the variability becomes an increasing problem as more is added to the electric grid.

When an area first adds a small percentage of wind and/or solar electricity to the electric grid (perhaps 10%), the electrical system’s usual operating reserves are able to handle the variability. These were put in place to handle small fluctuations in supply or demand, such as a major coal plant needing to be taken off line for repairs, or a major industrial client reducing its demand.

But once the quantity of wind and/or solar increases materially, different strategies are needed. At times, production of wind and/or solar may need to be curtailed, to prevent overburdening the electric grid. Batteries are likely to be needed to help ease the abrupt transition that occurs when the sun goes down at the end of the day while electricity demand is still high. These same batteries can also help ease abrupt transitions in wind supply during wind storms.

Apart from brief intermittencies, there is an even more serious problem with seasonal fluctuations in supply that do not match up with seasonal fluctuations in demand. For example, in winter, electricity from solar panels is likely to be low. This may not be a problem in a warm country, but if a country is cold and using electricity for heat, it could be a major issue.

The only real way of handling seasonal intermittencies is by having fossil fuel or nuclear plants available for backup. (Battery backup does not seem to be feasible for such huge quantities for such long periods.) These back-up plants cannot sit idle all year to provide these services. They need trained staff who are willing and able to work all year. Unfortunately, the pricing system does not provide enough funds to adequately compensate these backup systems for those times when their services are not specifically required by the grid. Somehow, they need to be paid for the service of standing by, to offset the inevitable seasonal variability of wind, solar and water.

[7] The pricing system for electricity tends to produce rates that are too low for those electricity providers offering backup services to the electric grid.

As a little background, the economy is a self-organizing system that operates through the laws of physics. Under normal conditions (without mandates or subsidies) it sends signals through prices and profitability regarding which types of energy supply will “work” in the economy and which kinds will simply produce too much distortion or create problems for the system.

If legislators mandate that intermittent wind and solar will be allowed to “go first,” this mandate is by itself a substantial subsidy. Allowing wind and solar to go first tends to send prices too low for other producers because it tends to reduce prices below what those producers with high fixed costs require.2

If energy officials decide to add wind and solar to the electric grid when the grid does not really need these supplies, this action will also tend to push other suppliers off the grid through low rates. Nuclear power plants, which have already been built and are adding zero CO2 to the atmosphere, are particularly at risk because of the low rates. The Ohio legislature recently passed a $1.1 billion bailout for two nuclear power plants because of this issue.

If a mandate produces a market distortion, it is quite possible (in fact, likely) that the distortion will get worse and worse, as more wind and solar is added to the grid. With more mandated (inefficient) electricity, customers will find themselves needing to subsidize essentially all electricity providers if they want to continue to have electricity.

The physics-based economic system without mandates and subsidies provides incentives to efficient electricity providers and disincentives to inefficient electricity suppliers. But once legislators start tinkering with the system, they are likely to find a system dominated by very inefficient production. As the costs of handling intermittency explode and the pricing system gets increasingly distorted, customers are likely to become more and more unhappy.

[8] Modelers of how the system might work did not understand how a system with significant wind and solar would work. Instead, they modeled the most benign initial situation, in which the operating reserves would handle variability, and curtailment of supply would not be an issue.

Various modelers attempted to figure out whether the return from wind and solar would be adequate, to justify all of the costs of supporting it. Their models were very simple: Energy Out compared to Energy In, over the lifetime of a device. Or, they would calculate Energy Payback Periods. But the situation they modeled did not correspond well to the real world. They tended to model a situation that was close to the best possible situation, one in which variability, batteries and backup electricity providers were not considerations. Thus, these models tended to give a far too optimistic estimates of the expected benefit of intermittent wind and solar devices.

Furthermore, another type of model, the Levelized Cost of Electricity model, also provides distorted results because it does not consider the subsidies needed for backup providers if the system is to work. The modelers likely also leave out the need for backup batteries.

In the engineering world, I am told that computer models of expected costs and income are not considered to be nearly enough. Real-world tests of proposed new designs are first tested on a small scale and then at progressively larger scales, to see whether they will work in practice. The idea of pushing “renewables” sounded so good that no one thought about the idea of testing the plan before it was put into practice.

Unfortunately, the real-world tests that Germany and other countries have tried have shown that intermittent renewables are a very expensive way to produce electricity when all costs are considered. Neighboring countries become unhappy when excess electricity is simply dumped on the grid. Total CO2 emissions don’t necessarily go down either.

[9] Long distance transmission lines are part of the problem, not part of the solution.

Early models suggested that long-distance transmission lines might be used to smooth out variability, but this has not worked well in practice. This happens partly because wind conditions tend to be similar over wide areas, and partly because a broad East-West mixture is needed to even-out the rapid ramp-down problem in the evening, when families are still cooking dinner and the sun goes down.

Also, long distance transmission lines tend to take many years to permit and install, partly because many landowners do not want them crossing their property. In some cases, the lines need to be buried underground. Reports indicate that an underground 230 kV line costs 10 to 15 times what a comparable overhead line costs. The life expectancy of underground cables seems to be shorter, as well.

Once long-distance transmission lines are in place, maintenance is very fossil fuel dependent. If storms are in the area, repairs are often needed. If roads are not available in the area, helicopters may need to be used to help make the repairs.

An issue that most people are not aware of is the fact that above ground long-distance transmission lines often cause fires, especially when they pass through hot, dry areas. The Northern California utility PG&E filed for bankruptcy because of fires caused by its transmission lines. Furthermore, at least one of Venezuela’s major outages seems to have been related to sparks from transmission lines from its largest hydroelectric plant causing fires. These fire costs should also be part of any analysis of whether a transition to renewables makes sense, either in terms of cost or of energy returns.

[10] If wind turbines and solar panels are truly providing a major net benefit to the economy, they should not need subsidies, even the subsidy of going first.

To make wind and solar electricity producers able to compete with other electricity providers without the subsidy of going first, these providers need a substantial amount of battery backup. For example, wind turbines and solar panels might be required to provide enough backup batteries (perhaps 8 to 12 hours’ worth) so that they can compete with other grid members, without the subsidy of going first. If it really makes sense to use such intermittent energy, these providers should be able to still make a profit even with battery usage. They should also be able to pay taxes on the income they receive, to pay for the government services that they are receiving and hopefully pay some extra taxes to help out the rest of the system.

In Item [2] above, I mentioned that when coal mines were added in England, roads to the mines were substantially improved, befitting the economy as a whole. A true source of energy (one whose investment cost is not too high relative to it output) is supposed to be generating “surplus energy” that assists the economy as a whole. We can observe an impact of this type in the improved roads that benefited England’s economy as a whole. Any so-called energy provider that cannot even pay its own fair share of taxes acts more like a leech, sucking energy and resources from others, than a provider of surplus energy to the rest of the economy.

Recommendations

In my opinion, it is time to eliminate renewable energy mandates. There will be some instances where renewable energy will make sense, but this will be obvious to everyone involved. For example, an island with its electricity generation from oil may want to use some wind or solar generation to try to reduce its total costs. This cost saving occurs because of the high price of oil as fuel to make electricity.

Regulators, in locations where substantial wind and/or solar has already been installed, need to be aware of the likely need to provide subsidies to backup providers, in order to keep the electrical system operating. Otherwise, the grid will likely fail from lack of adequate backup electricity supply.

Intermittent electricity, because of its tendency to drive other providers to bankruptcy, will tend to make the grid fail more quickly than it would otherwise. The big danger ahead seems to be bankruptcy of electricity providers and of fossil fuel producers, rather than running out of a fuel such as oil or natural gas. For this reason, I see little reason for the belief by many that electricity will “last longer” than oil. It is a question of which group is most affected by bankruptcies first.

I do not see any real reason to use subsidies to encourage the use of electric cars. The problem we have today with oil prices is that they are too low for oil producers. If we want to keep oil production from collapsing, we need to keep oil demand up. We do this by encouraging the production of cars that are as inexpensive as possible. Generally, this will mean producing cars that operate using petroleum products.

(I recognize that my view is the opposite one from what many Peak Oilers have. But I see the limit ahead as being one of too low prices for producers, rather than too high prices for consumers. The CO2 issue tends to disappear as parts of the system collapse.)

Notes:

[1] BP bases its count on the equivalent fossil fuel energy needed to create the electricity; IEA counts the heat energy of the resulting electrical output. Using BP’s way of counting electricity, electricity worldwide amounts to 43% of total energy consumption. Using the International Energy Agency’s approach to counting electricity, electricity worldwide amounts to only about 19% of world energy consumption.

[2] In some locations, “utility pricing” is used. In these cases, pricing is set in a way needed to provide a fair return to all providers. With utility pricing, intermittent renewables would not be expected to cause low prices for backup producers.

This entry was posted in Energy policy and tagged EROEI, EROI, fossil fuels, renewable energy, renewable subsidies. Bookmark the permalink.

Renewables may not be able to support the current population in modern growth oriented consumer cultures, but some analyses suggest they could support a gradually contracting population on a simpler, more local, more agrarian economy. When the impact of climate change on food production is taken into account this may be the most optimistic future that is achievable.

fifty years ago. The pincer’s grip combination of energy constraints and climate disruption coming will mean that the four horsemen will be in charge in the near future.

There is zero chance that the population projections of the U.N. for 2050 will eventuate..

And that was naughty? Well, for your information, no change in climate anywhere so far can be definitively shown to have been directly caused by continued use of fossil fuels, so no impact from such change can reasonably be attributed. Indirectly, of course, fossil fuels cause the heat island effect and support a huge population that is capable of drastically altering the landscape over extensive areas of the planet.

We may already have crossed critical tipping points that will lead to mass extinction. But even if that is not the case, desertification of land and ocean will lower carrying capacity down from 7 billion to 2 billion.

One can never be sure one hasn’t already crossed a tipping point. That’s part of the fun of life. The tree on the side of the hill grows one leaf too many and blows down in the next strong wind, the tippler at the bar has one drink too many, the school bully goes on taunting and taunting until his victim’s anger overcomes his fear setting off an explosion of rage that kicks seven colors of play dough out of the tormentor.

It is hard to argue against the idea that humans are currently exceeding the earth’s capacity to carry them. Even Prince Harry and Princess Meghan realize this and are limiting themselves to just two kids, who will probably only consume the equivalent in resources of what about two thousand children in India will consume over the same period, so well done Harry and Meghan for leading the way.

People who wish to stop using fossil fuels are welcome to go ahead and eliminate their use of fossil fuels. Then they can set an example for the rest of us to emulate if we choose. I’m not a vegan or a transsexual or a member of a religious sect, but I absolutely support the human rights of individuals to engage in veganism, transsexuality or any religious practice they desire (consenting adults and all that). In the same spirit, I respect the rights of the millions of ecologically aware and climate concerned people worldwide to live without using fossil fuels free from the oppression of established social norms. Yes, this is a campaign I feel I could support, even though I have no wish to join them. Oppressed fossil fuel users of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your carbon footprint!

I would bet less oil production, caused by anything, will bring down the banking system within a year or two.

Where a banking collapse will lead, nobody really knows because it has never happened since the Industrial Revolution began. We did come very close to collapse during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The documentaries about the GFC on YouTube are worth watching in order to gain an understanding of how dangerous some of the smartest people on the planet thought it was. And bad housing loans will pale in comparison to a shrinking global economy caused by not having more and more fuel available in order to keep the economy ever expanding. Without expansion, the capitalist financial system melts down from leveraged debts going bad.

The grid is finished. Accept it. Renewables will happen, because the alternatives will go away. And renewables are intermittent. So electricity will be generated and used locally, and won’t be used when it is not being generated.

Population collapse is also inevitable, for many reasons, not least that modern agriculture is impossible without massive use of nonrenewable resources, and when it goes away the soil it has destroyed will take decades, if not centuries, to recover.

And my own view about our predicament: what we could or might do is not relevant, because we won’t do it. And on the whole, I trust Nature to do a better job rebalancing the biosphere than the collective wisdom of Earth’s most greedy and parasitic species could ever hope to do. If at the end of that process said species has gone the way of the dinosaurs, perhaps that is indeed the best thing that could happen to a small blue planet.

πηγή https://ourfiniteworld.com/